Maria Farantouri was born in Athens οn November 28th, 1947. A harsh period for Greece, which before it manages to recover from the Second World War and the German Occupation, entered an equally bloody Civil War.

Maria’s childhood was full of hardships. Her parents were both islanders, her father from Cephalonia, and her mother from Cythera. By the time she was born they were living in the working-class suburb of Nea Ionia, an area that had been settled by refugees from Asia Minor in the 1920’s. One of the many children struck by the poliomyelitis epidemic that swept the world, she was separated, at two years old, from her parents and quarantined with other affected children in a sanatorium. This painful experience and the effects of the disease made her childhood years difficult.

Adolescence saw the beginning of Maria’s creative experience; through her participation in the choir of The Society of Greek Music, she understood that singing would become not only a path to follow but a way of life. The Society’s objective was to promote progressive music based on Greek culture and tradition and it was the spawning ground for many young artists who aspired to revive Greek music including Yiannis Markopoulos, Manos Loizos, Dionyssis Savvopoulos, Christos Leontis, Zakis and Panayiotis Kounadis. In this inspirational environment, Maria took her first steps in music and because of her rich contralto voice, soon left the choir to become a soloist.

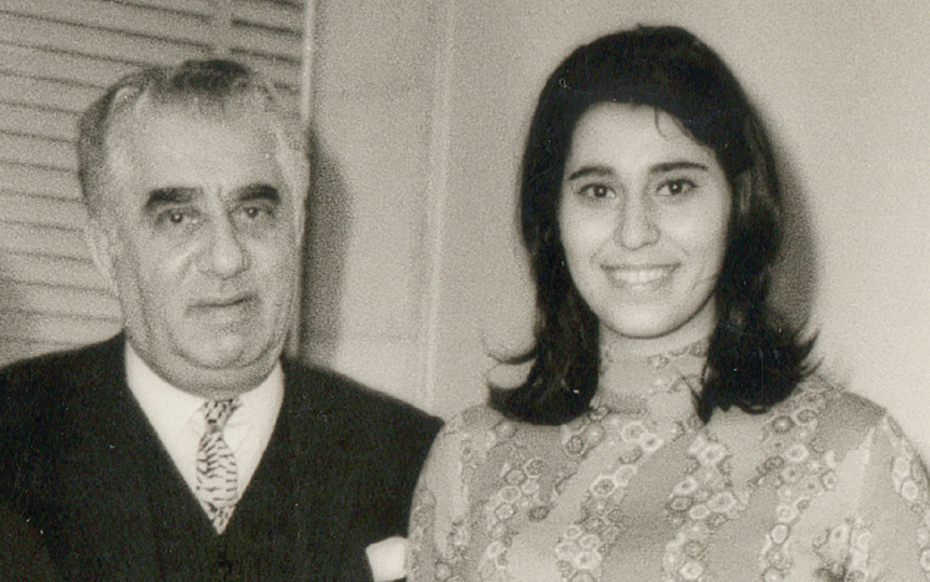

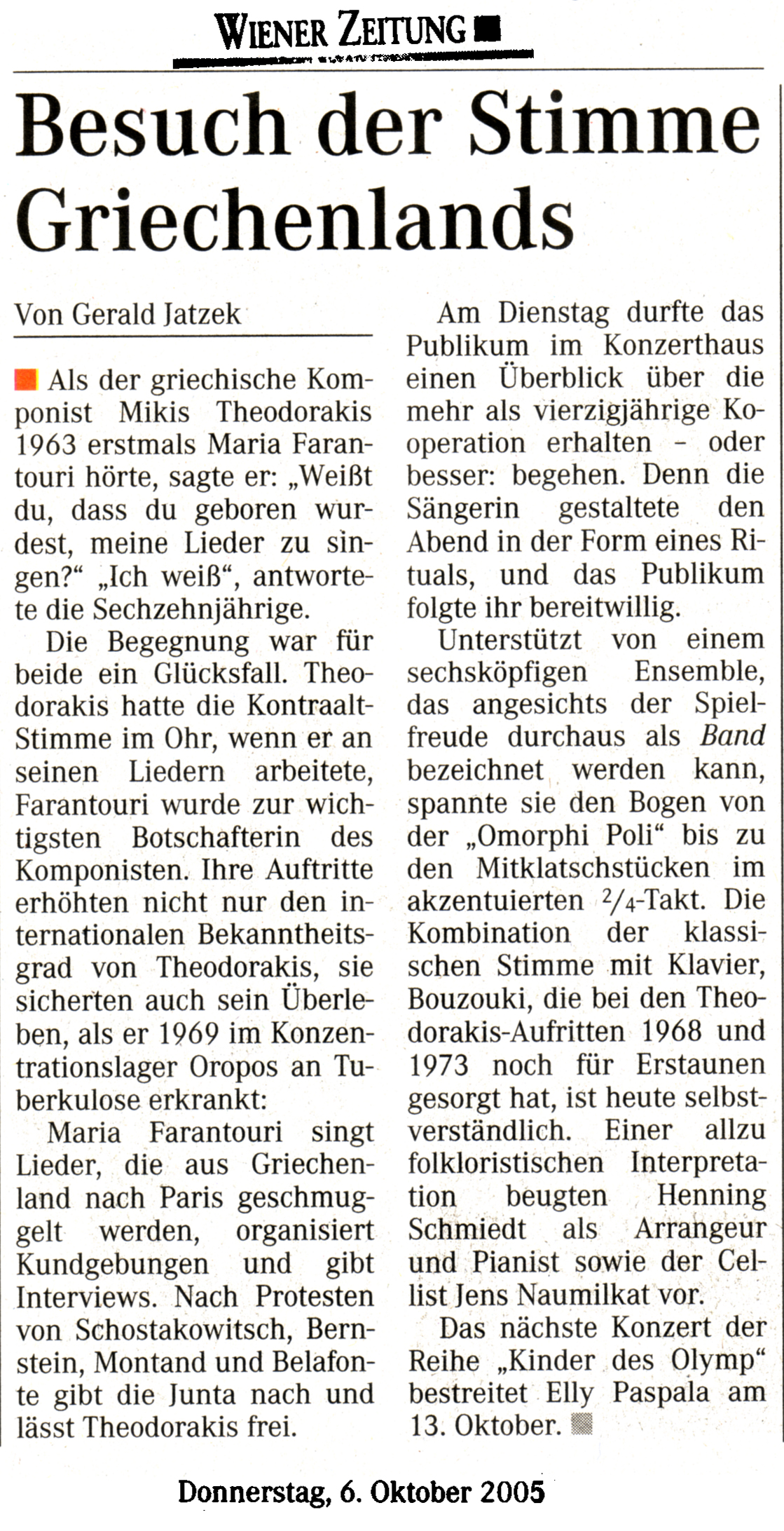

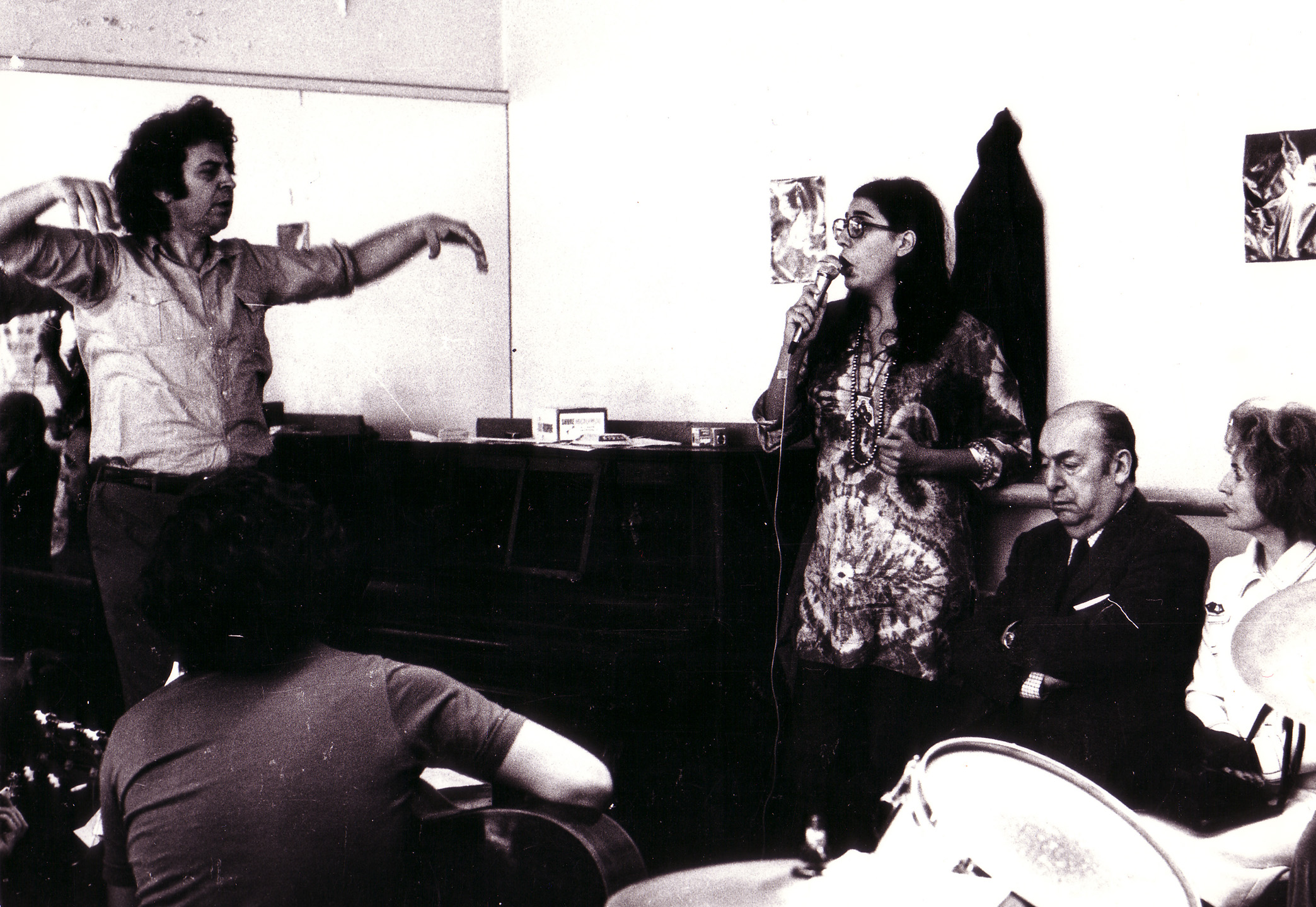

It was while she was singing with the Society choir, in 1963 that Mikis Theodorakis first heard Maria singing a song of his own entitled Grief. The composer was deeply impressed by the young singer and at the end of the concert he met her backstage: Do you know that you were born to sing my songs? he told her. I know was the immediate response of the sixteen-year-old singer. In the summer of the same year, after school had broken up for the summer vacation, Maria became a member of Theodorakis’s ensemble. Together with Grigoris Bithikotsis, Dora Yiannakopoulou and Soula Birbili, Maria encountered the magic of concert performance for the first time. Soon, her voice was heard at all important political and social events. Theodorakis’s new work The Hostage was performed at every peace demonstration, and with her militant young voice, Maria made the song The Laughing Boy known throughout Greece, and eventually, the world.

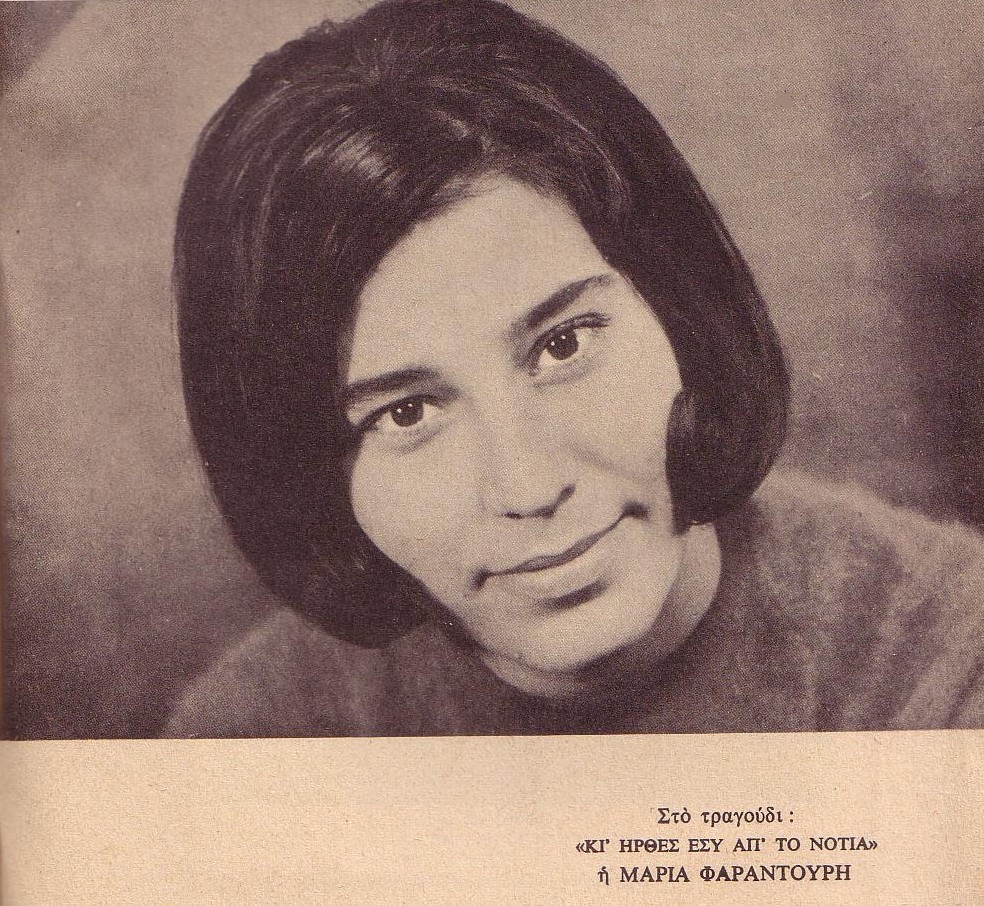

During the same period, two of the most famous actors of the Greek theater (Katina Paxinou & Alexis Minotis) were preparing a performance of Euripides’ Phoenician Women at Epidaurus for which Theodorakis had composed the music. Observing the rehearsals was an education in vocal practice and musical expression for the young Farantouri. At the same time, Maria was discovered by Manos Hadzithakis, who had just written the songs for the theatrical adaptation of Captain Michalis by Nikos Kazantzakis, presented by the troupe of Manos Katrakis. Having already recorded them with Υorgos Romanos, he decided to turn an instrumental piece into a song, especially to be sung by Maria Farantouri. Thus, You came with the North Wind became the first song by Manos Hadzithakis recorded by the young Farantouri. In the early 1990s, the composer decided to record the entire work with her. He arranged it for her voice, then he recorded the music alone, but when she was about to add her voice to the recording, the composer’s already fragile health began to deteriorate, and he soon passed away. Shortly after his death, Maria with Manos’s close collaborator Nikos Kypourgos, they finished the recording, but it still remains unpublished…

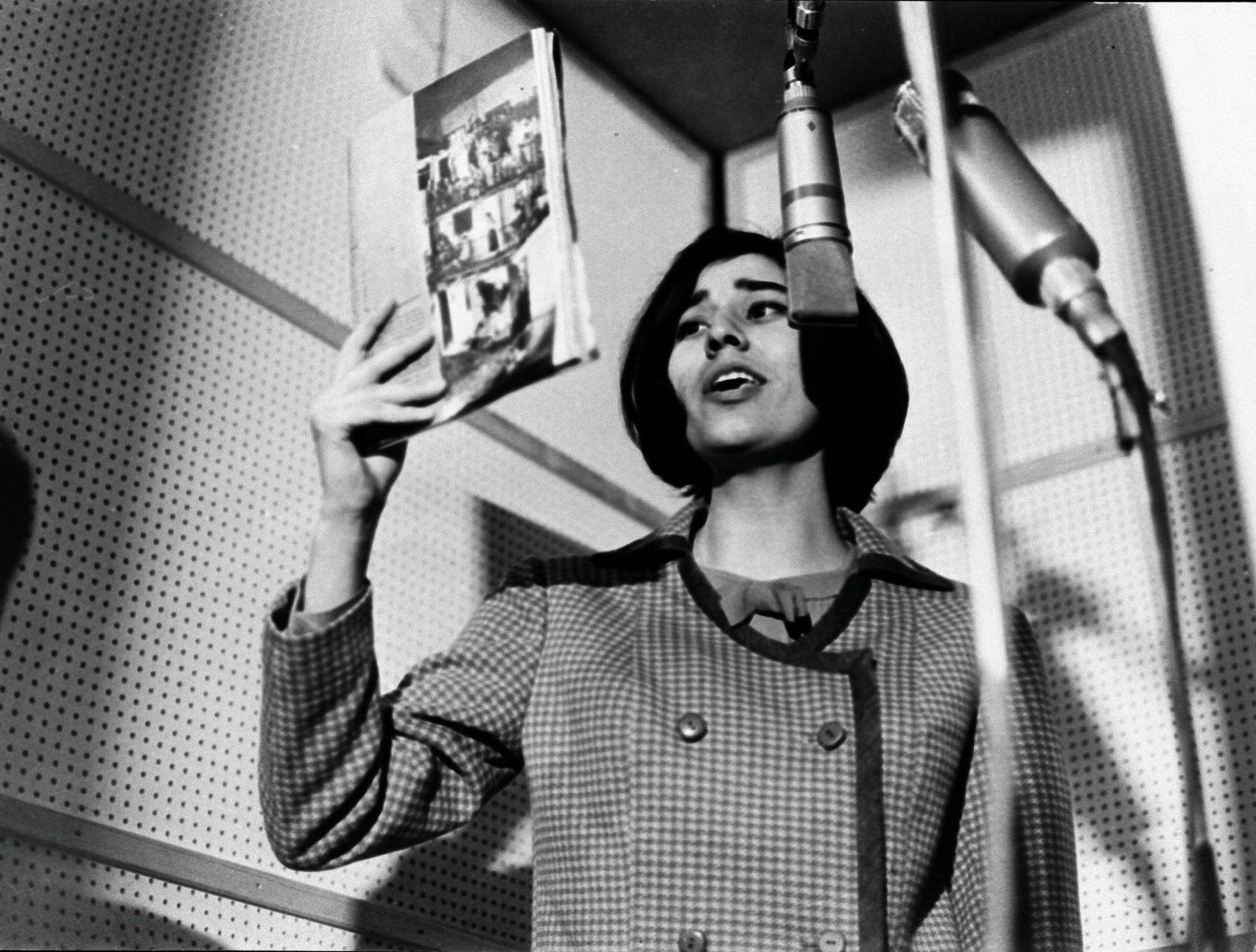

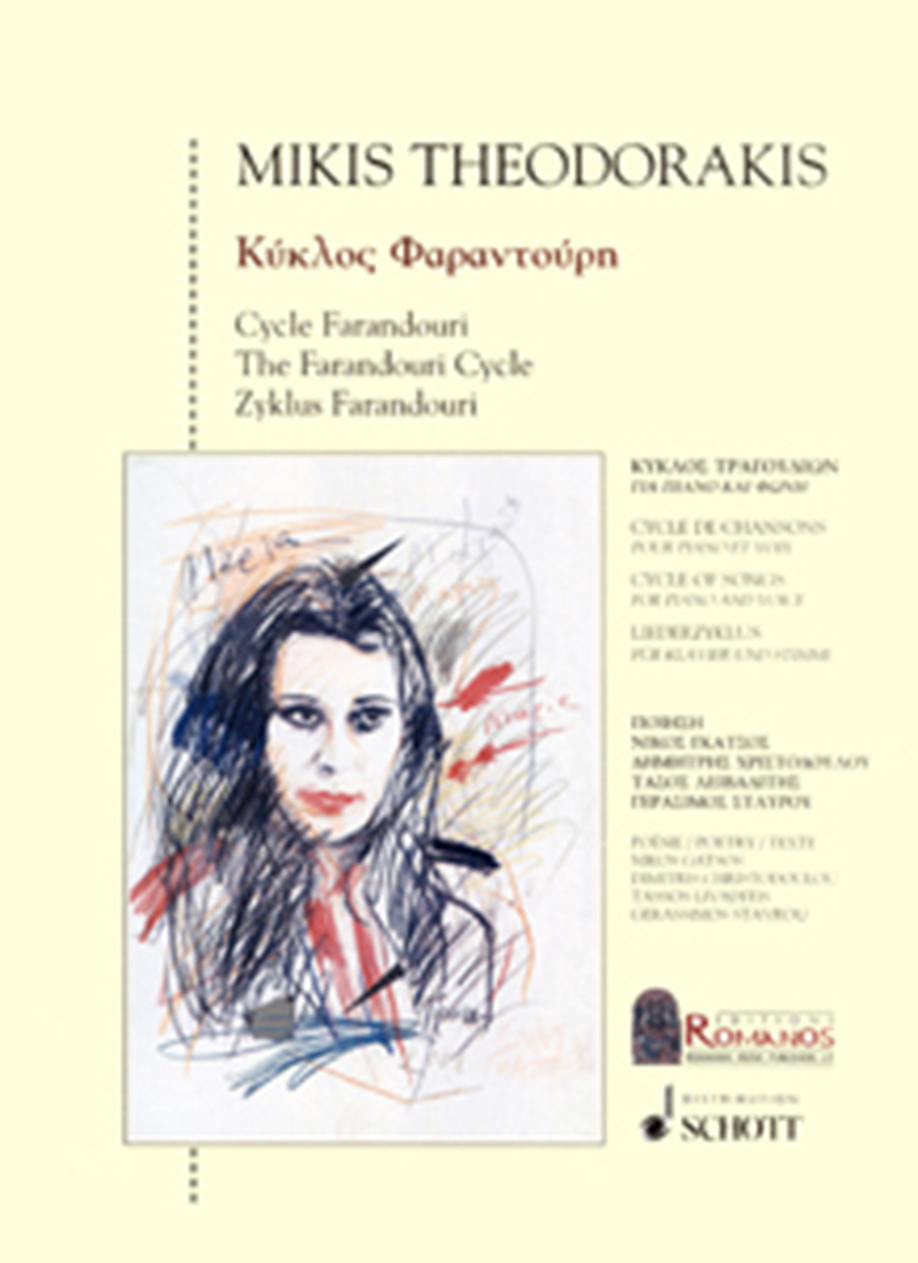

In 1965 Maria made her first professional recording of a song by Spyros Papas and Yiannis Argyris: Someone is Celebrating, with Lakis Papas accompanying. In 1966, the soundtrack of Harilaos Papadopoulos’s film, Island of Aphrodite was released with music by Theodorakis. From this came Maria’s first recording of Theodorakis: Blood-stained Moon – a setting of Nikos Gatsos’ poem. Shortly before this, Theodorakis had invited her to his house and played her the first work he had written specifically for her voice. It was called The Ballad of Mauthausen with lyrics by Iakovos Kambanellis and the song was to become identified with Maria’s voice throughout the world. Soon after, the composer wrote six more songs for Maria’s voice and named them Farantouri’s Cycle paying homage to the young artist who would become his major interpreter – his priestess! Although he has written many other songs for male and female voices, Farantouri remains the only artist to whom Theodorakis has dedicated a song cycle.

As an inseparable member of Theodorakis’s band, which toured in Greece and abroad, Maria visited the Soviet Union in 1966. There, the famous Russian composer Aram Illych Khachaturian heard her voice and asked her to stay on in Moscow for musical studies. But Maria followed Theodorakis instead on his musical travels. The live recordings made on the tour of the USSR would be regarded milestones in Greek music if they were available today.

Together with Theodorakis, who radically transformed Modern Greek music, especially songwriting, Maria Farantouri made the Greek public familiar with the poetry of the Nobel Prize-winning poets George Seferis and Odysseas Elytis and many other important Greek poets. The musical and political movement begun by Theodorakis and some of his colleagues did not end with the military coup d’état of 1967. The new regime banned Theodorakis’s music and after spending four months underground, he was arrested. Earlier, with on a paper chewing-gun wrapper, he had managed to send a short message to Maria, advising her to leave Greece and go abroad. She was just twenty years old when she left Greece for Paris, and she did what she considered the obvious thing to do; she sang in a great many non-commercial concerts, the profits from which went to the anti-dictatorship movement. She became a symbol of resistance and hope, and, sensitive to social problems, she took an active role in the women’s movement, in ecological activism and the struggle against drugs.

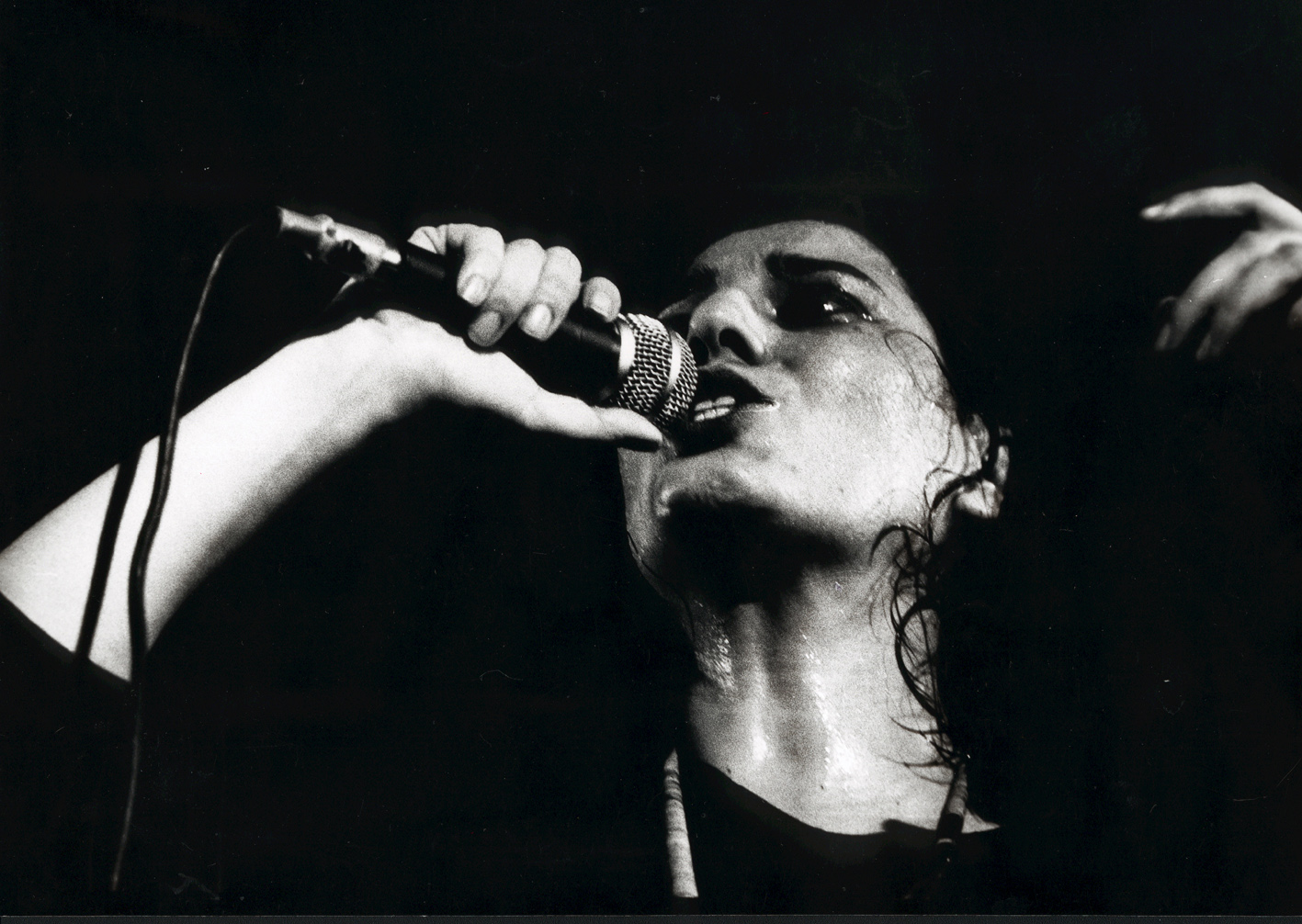

The international press called her “a people’s Callas” (The Daily Telegraph), and “the Joan Baez of the Mediterranean” (Le Monde). According to The Guardian, her voice was “a gift from the gods of Olympus”. Long reviews were devoted to her performances by enthusiastic critics who recognized not only the quality of her voice and the modest style of her performances, but also her strong character and social commitment. In the Greek context, at least, Maria represented a completely new style of singer – a self-aware woman.

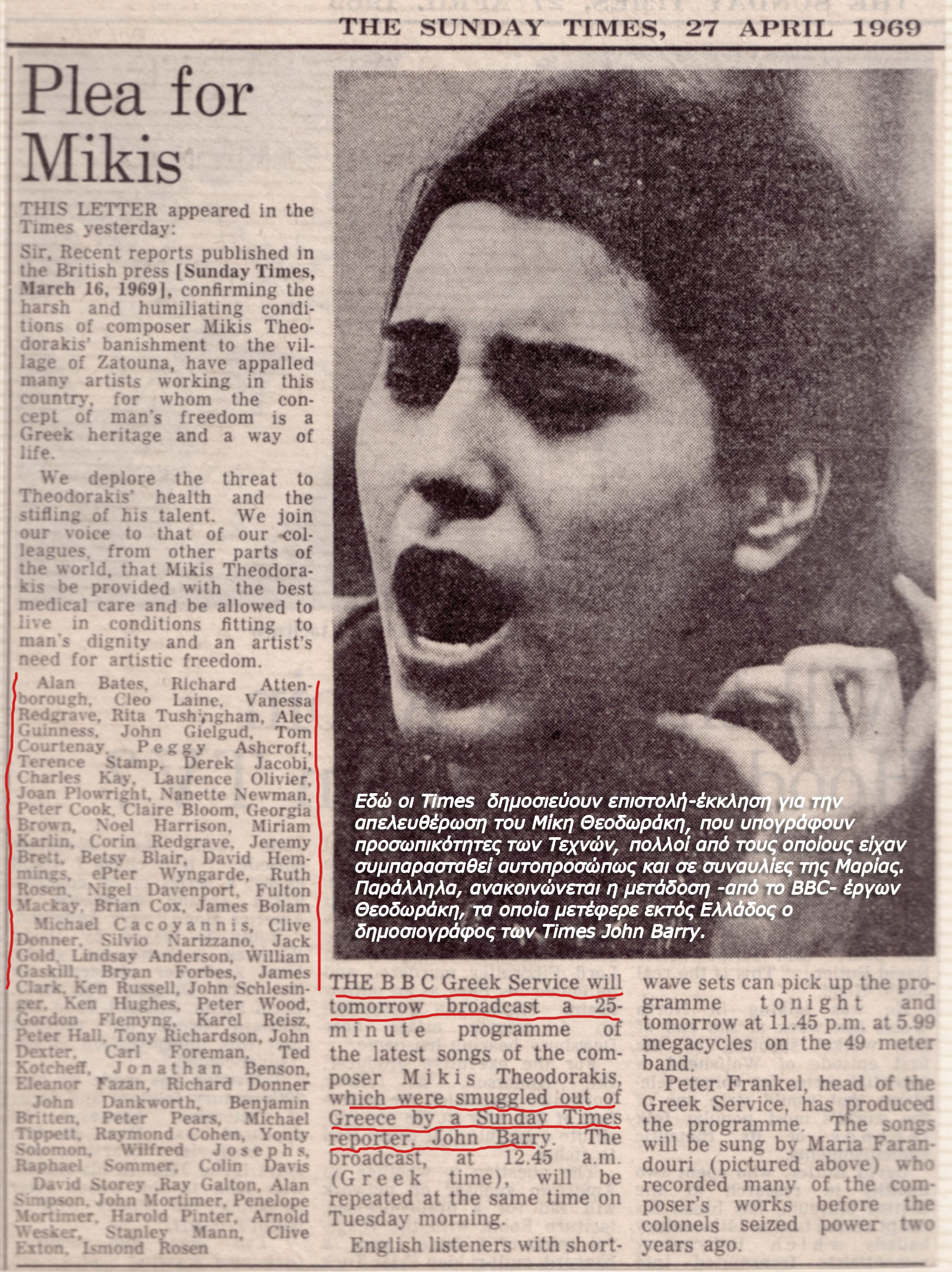

With her concerts in Europe and America, as well as her recordings, that were broadcast by the BBC and Deutsche Welle, Maria kept Theodorakis’s music alive along with the interest in the Greek struggle against dictatorship. The composer, exiled in the remote mountain village of Zatouna, secretly supplied her with tapes of his new songs which he recorded crudely on a small tape-recorder and smuggled to her. It was Maria’s responsibility to organize musical arrangements for the songs he had recorded, playing them on the piano and singing them himself. It was under these harsh conditions he first heard State of Siege, his setting of a poem by a woman prisoner, broadcast from London’s Roundhouse, on a radio he had kept hidden from his guards. At this historic concert Maria was supported by Greek artists such as Minos Volanakis, and actors from the musical Hair, who rushed from their show during one of the intervals to support their fellow artist. Sir John Gielgud, Alan Bates and Peggy Ashcroft also offered their help in a later concert Maria gave at the Albert Hall.

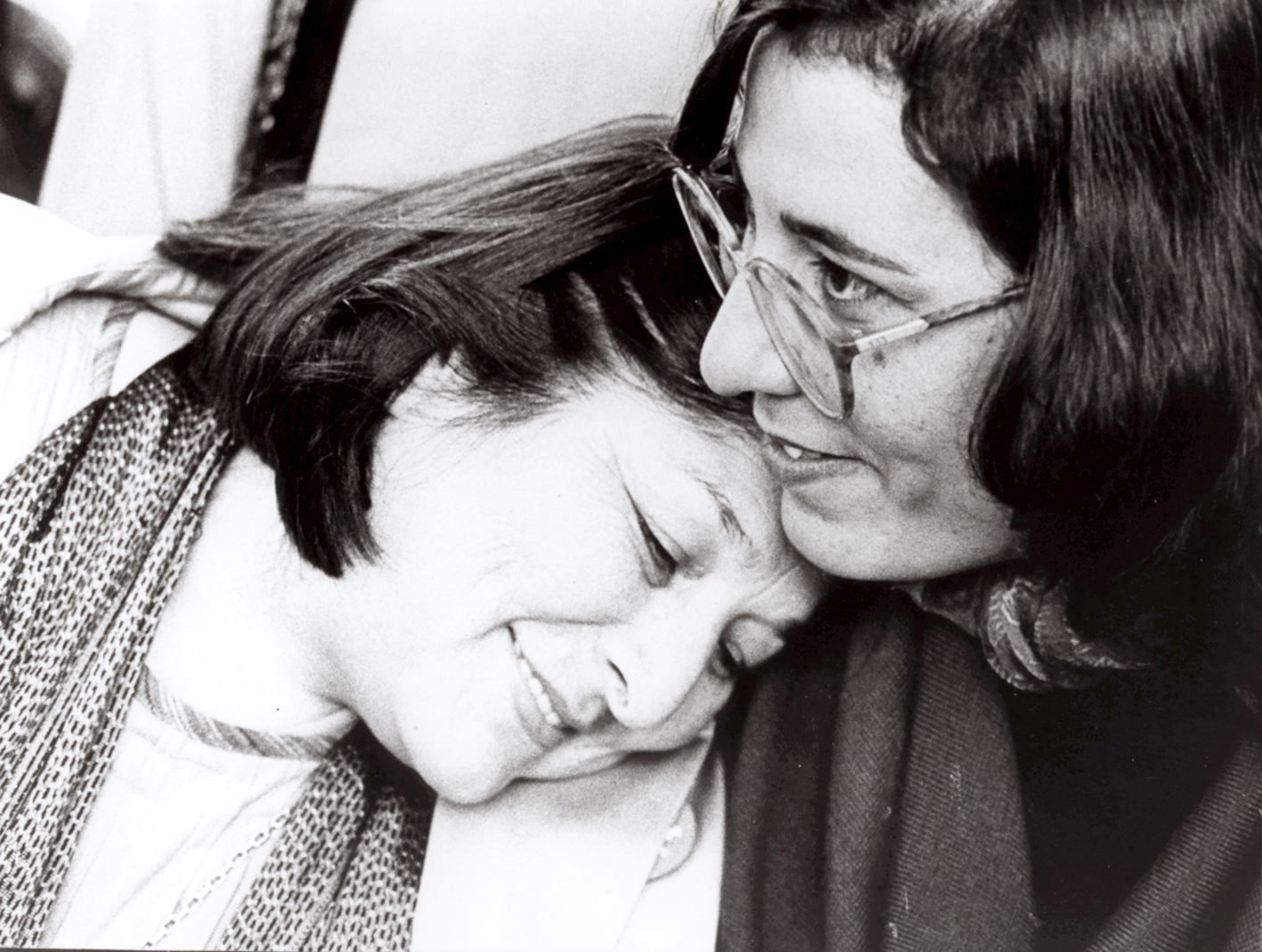

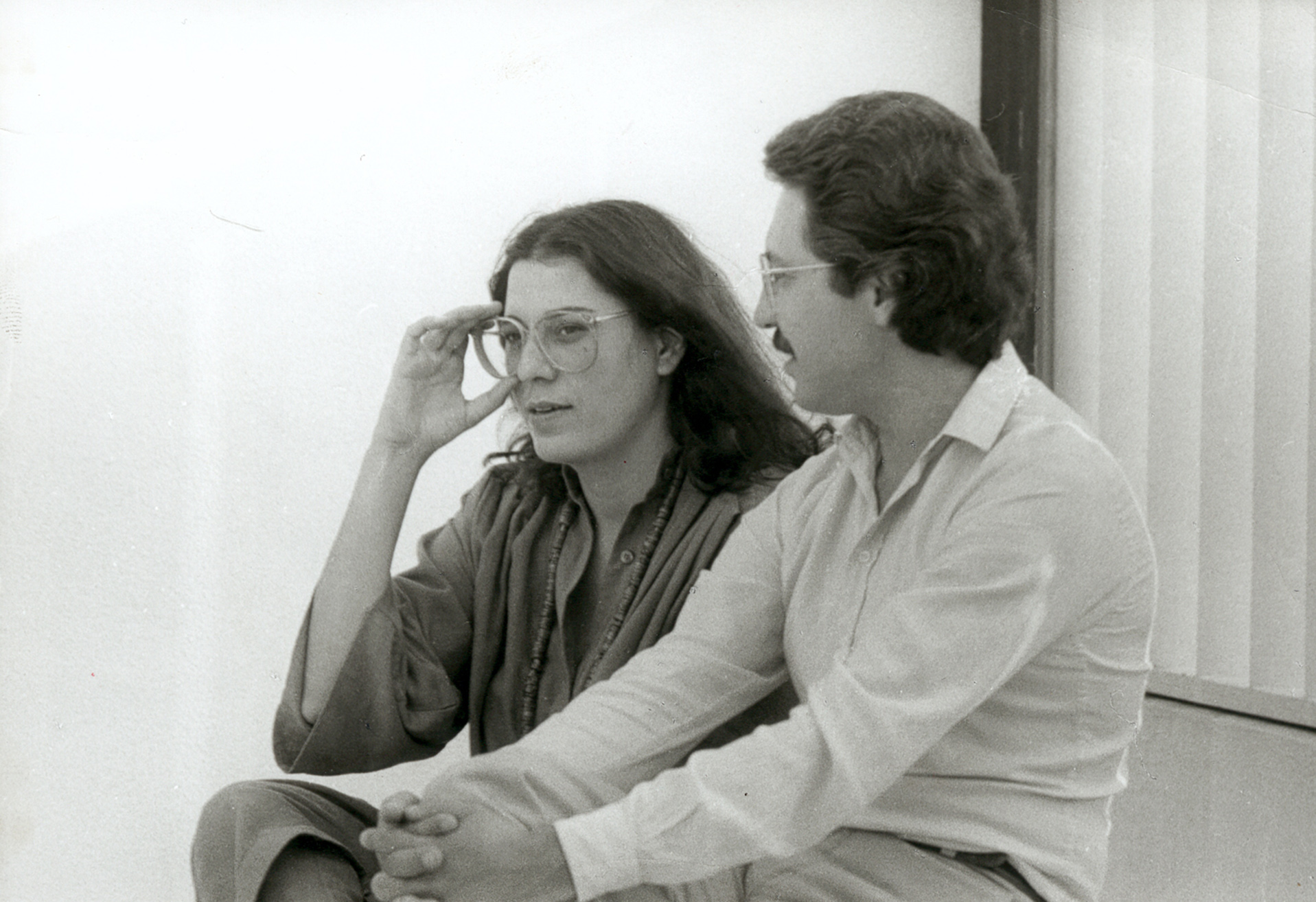

It was at this period that Maria met Telemachos Hitiris, a poet and student of philosophy at Florence, where she had been invited to give a concert by some Greek students. The years that followed and the birth of their son revealed that the couple had made a lifetime bond.

It was at this time, too, that Maria began collaborating with the composer Manos Hadzithakis, who was then working on a piece called The Age of Melissanthi, a composition based on his personal experience, and the hardships of his youth. The wounds left by the German Occupation were re-opened by the regime of the military dictators. Hadzidakis reserved a central role in this work for Maria, and subtitled his composition A Musical Story with Maria Farantouri. His work would not be finished until years later, but the creative course of Maria’s and Manos’s relationship had already begun.

It was through Hadzithakis’s intervention that Maria was able to come to Greece in 1972 to bid a last farewell to her father who died in that year. The military authorities deemed that a forty-eight-hour visa was sufficient for her to mourn her father. During these two days, however, Maria found time to visit the ancient theatre of Epidaurus, where she felt the pulse of her ancestors still beating freely – a breath of Greek freedom that she carried with her as she returned to her self-exile.

Two years earlier, after the intervention of international artists and writers, Theodorakis, whose health was precarious following his various imprisonments, exiles and house arrests, was released. With the assistance of the French politician Jean-Jacques Servan-Schreiber, he was taken to Paris, from where he began his ceaseless tours of Europe, North and South America, and the Middle East. Always at his side, Maria played a leading part in his concerts, which soon became a beacon of freedom for the exiled Greeks, and were supported by famous international artists, intellectuals, and other distinguished world figures. The Europeans stood by the exiled Greeks, embracing their struggle for freedom. The concerts, held in such venues as the Olympia, Salle Pleyel, Bobino, the Lincoln Center, the Albert Hall and the Salle Tchaikovsky in Moscow, to name a few, have become legendary. Not only did these concerts give courage to the Greeks, but they made foreign audiences familiar with Greek music, and with the creative genius of Theodorakis. Even today, concert halls abroad, especially in Europe, are packed whenever Maria Farantouri sings or when Mikis Theodorakis presents his classical compositions.

The concerts Maria gave abroad were recorded, and reached Greece secretly, usually inside different cover-sleeves, giving courage to those who were struggling against the junta. In the same way, without anyone noticing, the early work of the young composer Heleni Karaindrou, The Great Insomnia, a setting of poems by Yorgos Yeorgoussopoulos, was smuggled out of Greece. Maria’s voice was added to the recording in a London studio, and thus she put her stamp on the unique cycle of songs by Karaindrou, who was to become famous for her film soundtracks. On tour in the USA, Farantouri met the singer Fleri Dandonaki in New York, and their friendship continued until the Dandonaki’s agonizing death in 1998.

By the early 1970’s, London had become Maria’s adopted home, and it was there that she met the guitar virtuoso John Williams. The internationally renowned artist was impressed by her voice and presence and together they made an exquisite recording of Theodorakis’s Romancero Gitano, a setting of poems by Federico Garcia Lorca. A victim of Spanish fascism, Lorca had been an inspiration to Theodorakis, who set his poetry to music just before the Greek coup d’état. In 1971, with Maria’s voice, John Williams’ on guitar, and the Elytis’s brilliant translations, Lorca’s poems found an ideal interpretation.

In Paris, where Theodorakis established himself following his release, he was soon in touch with the avant garde of his time. He supported François Mitterrand -leader of the French Socialist Party- with his concerts and Maria made such an impression on the French leader that he was inspired to write about her in his book The Bee and the Architect. In it he compared her to Greece itself and to the goddess Hera, he found her strong, pure, and vigilant.

When the Greek dictatorship fell, Mikis Theodorakis and Maria Farantouri returned to Greece, where they gave truly moving concerts to Greek audiences who had experienced seven years of fear and repression. 125,000 people attended the performance of Theodorakis’s Canto General in the Karaiskakis Stadium alone. Maria and her colleague, the baritone Petros Pandis, who had had the privilege of rehearsing this work in Paris under the gaze of the poet Pablo Neruda himself, put their own stamp on this extraordinary work.

Maria has always made conscious choices, and from early in her career she succeeded in achieving artistic independence; as a self-inspired artist, she was able to negotiate her way through all sorts of songs. Her teacher, Elli Nikolaidi, always at her side, was a valuable aid in Maria’s music practice. Faithful to the path she had followed, she was careful to preserve high artistic standards and the quality of her choices as she began to enrich her repertoire after 1976. After seven years abroad she was also driven by a natural desire to advance her career. As a citizen and artist of the world she had been in contact with foreign artists and performed in international festivals with such noted singers as Juliette Greco, Mercedes Sosa, Myriam Makeba, Inti Illimani and Maria del Mar Bonet. She offered Greek audiences the results of her experience in her Songs of Protest from all over the World, a recording that not only found an immediate response but became a gold record.

Her acquaintance with the leading actor of the Berliner Ensemble, Ekkehard Schall, resulted in a fine collaboration for Maria’s performances of Bertolt Brecht’s songs. Maria was the first foreign artist accepted by German audiences as an interpreter of Brecht and in a language other than German. The performances she gave in Germany and later in Greece with Ekkehard Schall were enormously successful.

Maria’s singing also inspired foreign artists who sang her songs after listening to her recordings, giving them their own interpretation. The rock group Savage Republic arranged sections of The Ballad of Mauthausen as well as The Hostage, and the jazz musician Nels Cline dedicated an improvisation based on the song Soledad from Romancero Gitano to Maria, calling it Maria Alone (For Maria Farantouri).

Maria also renewed her collaboration with the Greek song-writer Manos Loizos at this time, with an album that characterized an era: The Negro Songs, based on the poetry of Yiannis Negrepontis. She also worked with the young composer Mihalis Grigoriou, who had set the poetry of Manolis Anagnostakis to music. Meanwhile her collaboration with Hadzidakis had been revived with the completion of Mellisanthi and the composition of new songs especially for her voice. Hadzidakis’s concerts in the Roman Agora of Athens, with Maria and younger singers who were taking their first steps as performers, were the musical event of the season.

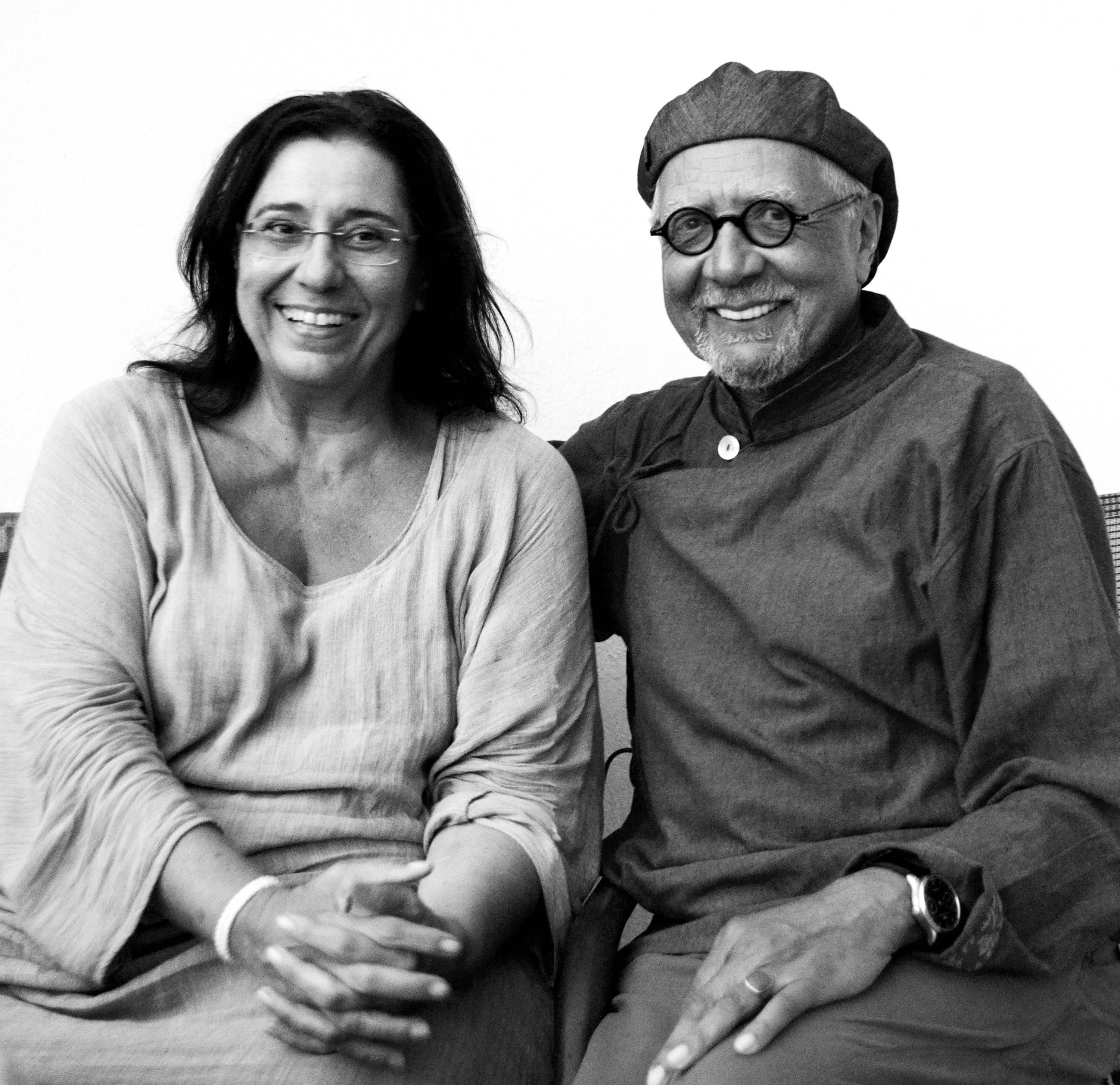

A longing for peace and friendship between Greece and Turkey led Maria to take the daring step of collaborating with the Turkish composer Zülfü Livaneli. Their concerts in Athens were embraced by the public, who clearly revealed their weariness with the long confrontation between the two nations and their desire for reconciliation and peaceful co-existence. The same enthusiasm, if not greater, was displayed by Turkish audiences.

In 1981 she traveled again with Theodorakis to Cuba. Their concerts before the musically aware Cuban audience, including Fidel Castro himself, were so successful that the Cuban leader issued an open invitation to the Greeks to perform a new series of concerts the following year.

1985 marked the beginning of a new chapter in Maria’s life, with the birth of her son Stefanos on October 28th (National Independence Day in Greece). Commenting wittily in the magazine Tetarto, Manos Hadzidakis noted: “National Independence Day (usual, annual). Total eclipse of the moon (unusual). The son of Maria Farantouri and Telemachos Hitiris was born. The only event worth mentioning. I wish him a long and prosperous life. Our best wishes. From the bottom of our hearts. With all our love”.

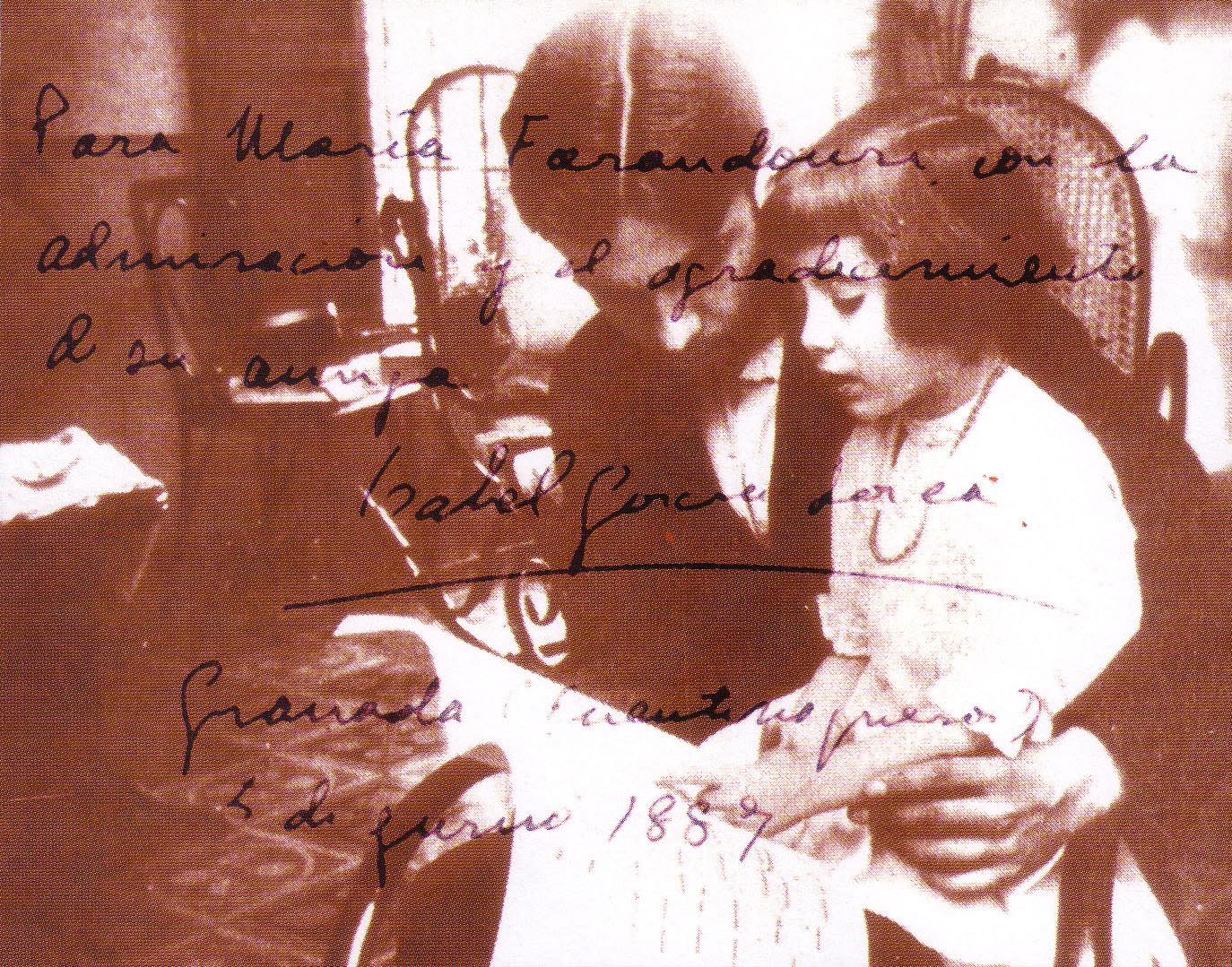

A period of relative withdrawal from artistic engagements followed the birth of Stephanos. Maria worked rarely and selectively. Her most important collaboration was with the Israeli Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Zubin Mehta at the Herod Atticus Odeon of Athens, in what had become the classical The Ballad of Mauthausen. Later she would find herself again under his direction in Paris for the celebration of the Millennium under the auspices of UNESCO. In 1987 she would have the moving experience of performing Romancero Gitano in Fuente Vaqueros, in the house where Lorca was born. Present at the concert were the sister of the poet and his artist friend Jose Caballero. In 1987, again at the Herod Atticus Theatre, she participated in a concert with the Norwegian saxophonist Jan Garbabek in a concert in which Eleni Karaindrou presented musical themes and songs from her film scores.

In 1989 the political situation in Greece became unstable. Prime Minister Andreas Papandreou, leader of the Socialist Party, was under attack from the opposition. Election succeeded election without the formation of a stable government. At that time Maria felt that she had to support the historic leader of the Socialist Party against what proved to be slanderous attacks. Responding to his invitation, she offered herself as a candidate for office and elected as a member of the opposition, she worked with Melina Mercouri and Stavros Benos on cultural issues.

Motherhood and politics could not keep her long from her art and in 1990 she worked with Cuban composer Leo Brouwer on a double album of international repertoire, including songs written especially for her voice by Vangelis Papathanassiou.

Although her collaboration with Theodorakis has continued until today, including on his most recent works, Maria actively seeks out the new generation of young composers. For example, she sang The Diary for Passer-by at the End of the Century, by Pericles Koukos, a setting of the poetry of Christoforos Christofis at the Athens Music Hall in 1996. Three years later, seeking a creative new direction, she proposed collaboration with two of her younger colleagues, Savina Yiannatou and Elli Paspala. Supported by the musical arrangement of the pianist Takis Farazis and with the participation of musicians David Lynch and Haig Yazidjian, the show they put together was such an artistic and commercial success that they were able to keep it going for two years.

In 2000, after years of absence, the avant-garde composer Lena Platonos, who was regarded by many as the only significant descendant of Manos Hadzidakis, returned to the recording studio, and recorded exclusively with Maria. In August 2001, when Athens had emptied for the summer vacation, Maria filled the Herod Atticus Odeon, performing with the Orchestra of Colours under the baton of the conductor Miltos Loyiadis in a program called A Century of Greek Song. In June 2003, nine years after the death of Manos Hadzidakis, once again in the Roman Odeon, Maria sang in the completed version of his Amorgos, a setting of the poetry of Nikos Gatsos. Her collaborations with symphony orchestras in Greece and the world as well as with soloists of the classical repertoire, as with the distinguished pianists Dora Bakopoulou, Giannis Vakarelis and George Lazaridis, never stopped.

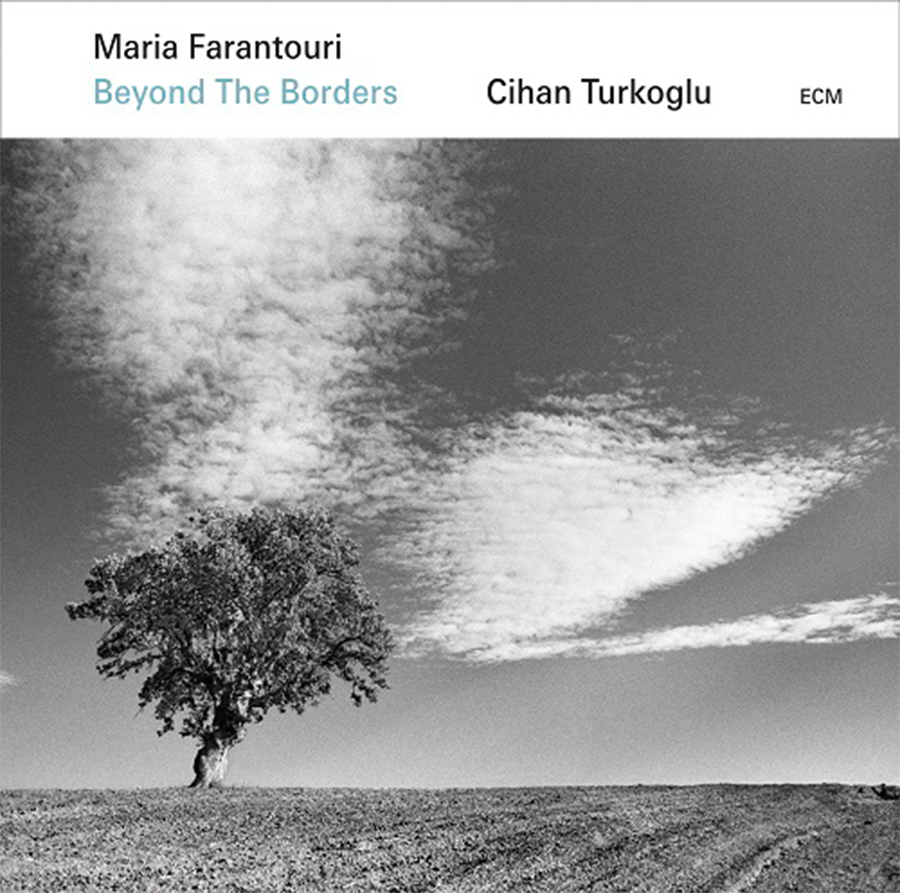

For the last twenty-five years many of Maria’s performances abroad and in Greece have been supported by the German band Berliner Instrumentalisten including the musicians Henning Schmiedt (piano), Volker Schlott (saxophone/flute) and Jens Naumilkat (cello) while in Greece by Takis Farazis (piano) and David Lynch (saxophone / flute). With these musicians, Maria has given a new dimension to the traditional Greek rembetiko (traditional urban songs often likened to the Blues), to Byzantine music, to old and new Greek and international repertoire. At the same time, she continues to reach out to international musical trends, such as ethnic music and even jazz by collaborating with the American jazz legend Charles Lloyd: their concert in the ancient Herod’s Atticus Odeon was recorded by Manfred Eicher on behalf of ECM and the Athens Concert was released on cd in September 2011. Seven years later she renewed the collaboration with ECM which released her CD on a wider Mediterranean repertoire with the young Turkish composer Cihan Türkoğlu.